Our Vision

Every child should have access to the help they need to maximise their learning potential within the school environment, without the inhibition of finances.

Our Mission

Empowering whānau to access the help required to holistically support all our tamariki.

Our Strategy

Support

- Become a visible presence around schools and pre-schools.

- Help whānau and educators navigate the services available.

- Direct whānau to the appropriate organisation that best suits their needs.

- Connect and collaborate with other organisations both locally and nationally to optimise the holistic well-being of our tamariki.

Screen

- Set up a cost-effective screening service for neurodiversity and processing disorders.

- Use a multidisciplinary team (including but not limited to a Behavioural Optometrist, Speech and Language Therapist, Occupational Therapist, Educational Psychologist and Specialist Educators) to review and assess each child identified as needing support and make a support plan of action and a diagnosis, if appropriate.

- To present this support plan in a simple format that all educators and whānau can understand and act on.

Educate

- Work with other organisations and individuals to facilitate cost-effective workshops to educate whānau and educators about learning differences.

Enable

- Enable all tamariki to access the specialist help required by attempting to remove the financial barriers associated.

- Enable the multidisciplinary team to collaborate in an effective, cohesive way that is completely child-centric and does not overload the individual child.

- Work with the local schools to action putting any support plans into place.

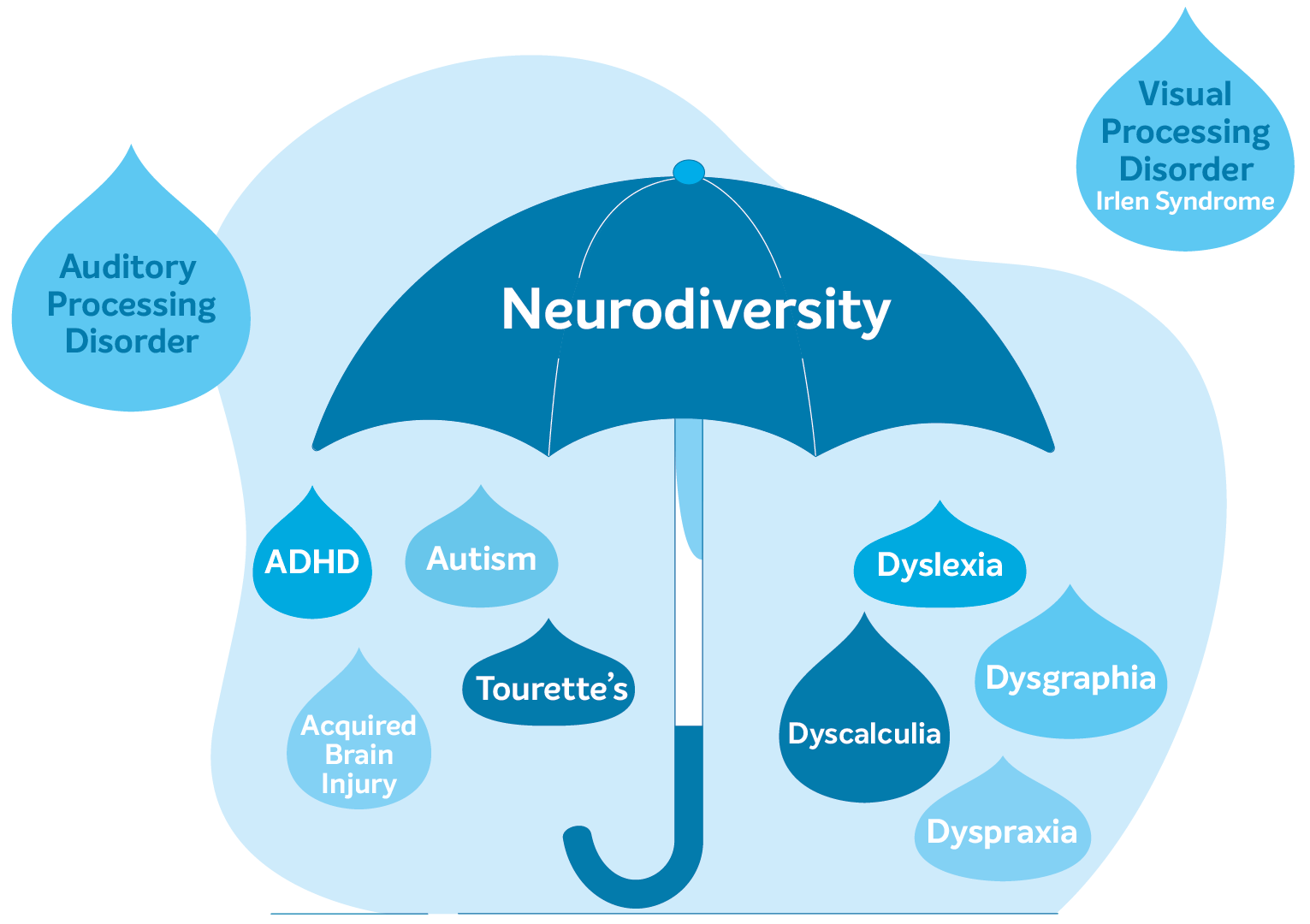

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity is an umbrella term that encompasses specific learning differences including Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Dysgraphia and Dyspraxia as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism and Tic Disorders such as Tourette’s.

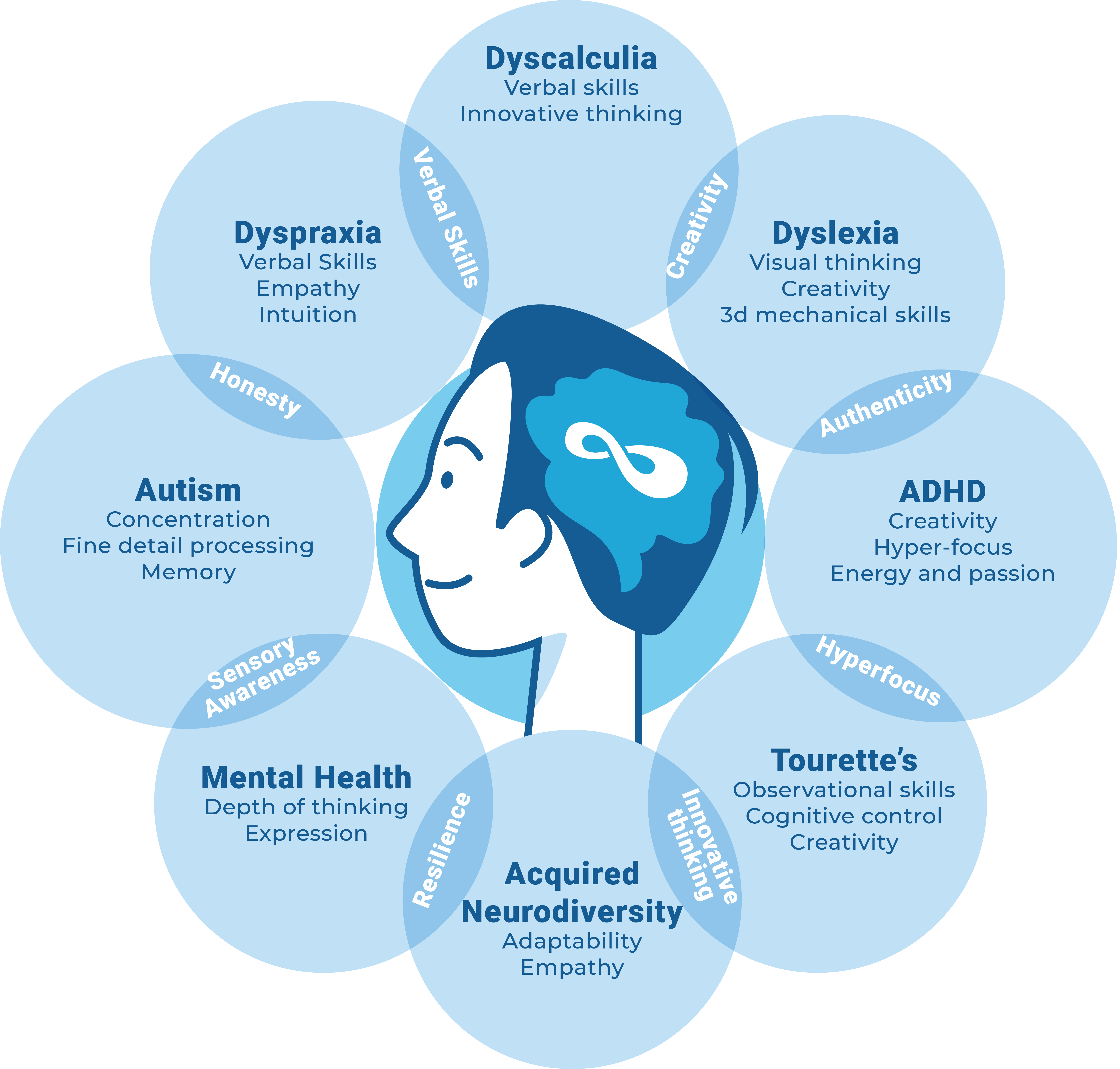

It recognises the fact that the neurodivergent individual has a brain that is wired differently in some way to the neurotypical individual. The term attempts to emphasise the positives of this different wiring and recognise the fact that the neurodivergent individual may have many unrecognised talents. It is also an attempt to move away from the idea that these individuals are in some way disabled or have a lower intellect.

The term recognises the fact that these differences often overlap and do not necessarily occur in isolation.

Tourette Syndrome

Tourette Syndrome (TS) or Tourette’s is a neurological diversity. Although genetic, not all children that inherit the various genes that could increase the risk of developing TS will display the traits that are associated with this difference. Environmental factors that interact with this genetic material as the brain is developing may also influence the risk of developing TS. Tourette’s is on the spectrum known as Tic Disorders.

It is characterised by physical (motor) and vocal tics that are involuntary and repetitive and range from mild to extreme in severity. Individuals can have singular tics, however, both motor and vocal tics need to have been present concurrently in an individual for at least a year and before the age of 18 before a formal diagnosis of Tourette’s can be made.

Although TS occurs in childhood, diagnosis may not be made until adulthood in many cases. Only a small number of people will ever be diagnosed with TS because the majority will have such mild tics that they may not even be aware that they have this difference.

TS evokes tics that are changeable and different for each individual. They will vary in frequency and severity throughout a person’s lifetime and are often described to ‘wax and wane’.

Motor and vocal tics are categorised into two types; simple and complex.

Simple motor tics are fast and meaningless. Examples include eye blinking or rolling, facial grimacing, nose twitching, shoulder shrugging, arm jerking, head jerking, head nodding, finger movements, mouth opening, jaw snapping and rapid jerking of any part of the body.

Complex motor tics tend to be slower and may appear to be purposeful. Examples include hopping, jumping, touching objects, twirling, gyrating, bending, head banging, kissing, licking, pinching, facial gestures, copropraxia (repeating extreme gestures) and echopraxia (imitating actions of others).

Simple vocal tics tend to display as noises that often appear as just ordinary sounds. Examples include sniffing, coughing, throat clearing, spitting, snorting, screeching, barking, grunting, clacking, whistling and sucking sounds.

Complex vocal tics are much more intrusive and can include repeating certain words or phrases such as “oh boy” or repeating a phrase until it sounds ‘just right’. Other examples include making animal noises, muttering under one’s breath, complex breathing patterns, stuttering, coprolalia (saying inappropriate things at inappropriate times), palilalia (repeating their own words), echolalia (repeating sounds and words said by others) and variations in speech like accents, loudness, rapidity, tones or rhythms.

Although individuals living with TS often face many challenges including at school, at home and socially, they often demonstrate a unique set of strengths. Some of these include being perceptually acute, creative, energetic, successful and quick to complete tasks they enjoy, able to exhibit a good sense of humour and they are often empathetic.

Tourette’s is often associated with and can coexist with other disorders such as ADHD and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). It affects approximately 0.1% of children in New Zealand.

Autism

Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference that affects cognitive, sensory and social processing. This means that autistic people think, behave, communicate and interact differently in the world.

Autism is described as a spectrum condition which tries to demonstrate that autistic individuals are affected by varying degrees. No two autistic individuals are the same. Some autistic people, for example, do not use spoken language while others have excellent spoken language skills but may struggle to understand what other people mean.

In New Zealand, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is the term used in diagnosis. Some autistic people prefer to use the term ‘autism’ as they dislike the negative meaning implied by the word ‘disorder’. This is compounded by the fact that autism is not an illness or a disease that can be ‘cured’ and research into ways to eliminate autism or treatments which aim to conform autistic behaviours causes offence, as many autistic adults consider that being autistic is fundamental to their identity.

While all autistic people share some common differences in the way they see, hear and feel the world, they are all unique. They have different abilities, strengths and challenges which affect their everyday life in different ways at different ages and in different environments.

Autism can often coexist with other neurodiversity, such as dyslexia and ADHD, as well as mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression. Although some autistic individuals can be very intelligent, some can also have intellectual disabilities.

As a consequence of these differences and the impact of other conditions, autistic people vary greatly in the amount of support they need to lead a fulfilling life as part of their community. While some people will have more subtle differences, others will have complex needs requiring more intensive support.

No definition can truly capture the range of characteristics autistic people experience in the world. However, autistic people may experience some of these common challenges:

- Social communication and interaction issues

- Repetitive and restrictive behaviour

- Over or under-sensitivity to sensory input such as sound, light, taste or touch

- Highly focused interests or hobbies

- Anxiety

- Meltdowns and shutdowns

The behaviours and challenges typically associated with autism are often as a result of differences in thinking and processing information.

Some signs of autism in young children include:

- Not responding to their name

- Avoiding eye contact

- Not smiling when smiled at

- Not talking as much as other children

- Repeating the same phrases

- Becoming very upset if they do not like something such as a certain taste, smell or sound

- Stimming or repetitive movements such as hand flapping, finger flicking, hair pulling, body rocking or even vocalisations such as whistling, grunting or muttering

Some signs of autism in older children include:

- Difficulty in expressing emotions

- Finding it hard to make friends or preferring to be on their own

- Difficulty in understanding what others are thinking or feeling

- Preferring a strict daily routine and becoming distressed if it changes

- Having a particular special interest in certain subjects or activities

- Becoming very upset if you ask them to do something

- Taking things very literally so they may not understand sarcasm or abstract concepts

Autism can sometimes present differently in girls and boys. Autistic girls may be quieter, may hide or mask their feelings and may appear to cope better with social situations. This can mean that girls can be harder to diagnose.

Autistic people may experience various challenges but they will also display a range of strengths and abilities. These can include:

- Precision and attention to detail

- Ability to concentrate and deeply focus on tasks

- Good visual thinkers and learners

- Excellent ability to absorb and retain facts

- Logical, methodical thinkers

- Innovative problem solvers

- Exceptional honesty, integrity and reliability

Autism affects 1-2% of the population.

Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a specific learning difference which primarily affects reading and writing skills. However, it does not only just affect these skills.

Although dyslexia is a problem with decoding words and their meanings, other aspects include difficulties with auditory and visual perception (how our brain interprets or gives “meaning” to what we hear and see), planning, organisation, fine motor skills, short-term memory and concentration. Even just some of these can make it really challenging to follow multiple instructions, turn thoughts into words and complete work on time.

However, despite being slower to process and understand language, people with dyslexia are stronger in creative areas such as problem solving, empathy, leadership and lateral thinking (thinking “outside the box”).

Dyslexia affects approximately 10% of New Zealand’s population.

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a specific learning difference that means that making sense of numbers and mathematical concepts is difficult. People with dyscalculia can lack an “intuitive feel” for numbers and struggle to learn basic number facts and procedures. It may also affect short-term, long-term and working memory.

These difficulties can affect day to day activities such as following directions, keeping track of time and dealing with finances.

However, like dyslexia, people with dyscalculia can display strengths in creativity, strategic thinking, practical ability, intuitive thinking and problem solving. Some can even have a “love” of words.

It affects approximately 6% of the population and coexists with dyslexia in 50% of cases.

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is a language based specific learning difference. One of the main signs of dysgraphia is messy handwriting.

Writing requires a complex set of fine motor and language processing skills. For people with dysgraphia, just holding a pen and organising letters on a line is difficult. This can lead to problems with spelling, putting thoughts on to paper and poor handwriting.

However, people with dysgraphia also display strengths in reasoning, problem solving and enhanced listening skills, recalling of oral details, memorisation and storytelling.

Like all the other specific learning differences, it can coexist with other differences.

Dysgraphia affects 5-17% of the population.

Dyspraxia

Dyspraxia is sometimes known as Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). It affects fine and/or gross motor coordination in children and adults.

An individual’s coordination difficulties affect everybody in different ways. They may affect participation and functioning of everyday life skills in education, work and employment. Children may present with difficulties with self-care, writing, typing, riding a bike and play as well as other educational and recreational activities.

The Dyspraxia Foundation in the UK recognises that there are also many non-motor difficulties associated with dyspraxia that can have an impact on daily life activities. These include memory, perception and processing as well as additional problems with planning, organising and carrying out movements in the right order in everyday situations.

Despite all of this, many people learn to adapt to the everyday struggles and that can lead to some very positive results such as being very creative, finding alternative ways to learn, have outstanding determination, a great sense of humour, very empathetic, unique problem solvers and possibly become very motivated individuals.

Dyspraxia affects approximately 6-10% of the population.

Processing Disorders

Processing disorder is a broad term used to describe a range of issues related to a person’s ability to process information. Processing disorders, such as Auditory Processing Disorder, Visual Processing Disorder and Sensory Processing Disorder are conditions in which the brain has difficulty interpreting and responding to the information that comes through the senses (i.e. what we see, hear, smell, taste or touch). If the brain cannot properly process the auditory, visual and/or sensory information that it receives, a child’s ability to learn and thrive in an academic setting is affected and this often leads to low self-esteem and socialisation difficulties.

Auditory Processing Disorder

Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) is when the brain has difficulty interpreting and responding to what the ears “hear”. In APD, the ears function normally and hear sounds well but the brain has difficulty processing and understanding what is heard.

As a result, a standard hearing test cannot detect APD and those with APD can have difficulty in the following areas:

- Understanding and remembering complex verbal information or instructions

- Listening to speech, especially in noisy settings

- Processing and remembering spoken information

- Learning language, spelling, vocabulary, reading or writing

- Distinguishing between tone of voice and other subtle differences in speech

- Sensitivity to noisy situations

These difficulties can clearly impact a child’s ability to function optimally at home and in the classroom. Although APD can be treated, it can coexist with specific learning differences such as dyslexia and dysgraphia.

It is estimated that APD affects 6.2% of children in New Zealand.

Visual Processing Disorder

Visual Processing Disorders occur when the brain has trouble making sense of what the eyes “see”. They are not to be confused with a visual impairment where there may be an issue with blindness, poor sight or the actual functioning of the eyes. In fact, a child could have perfect 20/20 vision and pass a sight test but still be unable to distinguish between two objects or make sense of symbols on a page.

Visual processing disorders can present in a number of ways and no two children will face the same challenges. Some may struggle to judge distances whilst others may have difficulty assessing colours, size or orientation. Spatial awareness is fundamental to visual processing and so problems here could lead to a child becoming easily disorientated and lost or struggling with fine and gross motor skills.

There are a number of skills that make up the ability to process visual information and where these are under-developed, they can be learnt and developed through vision therapy and aided with prescription glasses or colour tinted lenses.

Visual processing disorders are not classed as a learning difference but they can be mistaken for dyspraxia, dysgraphia, ADHD and dyslexia. However, they can also coexist with neurodiversity and can therefore, have a negative impact on a child’s self-esteem, confidence and performance at school.

80% of learning is visual. However, 64% of children have an undiagnosed visual problem that affects their ability to perform at school and in sports.

Irlen Syndrome

Irlen Syndrome is often referred to as a “perceptual processing disorder” suggesting that the brain is unable to properly process visual information from the eyes because of sensitivity to certain wavelengths of light. It is not an optical problem nor is it the same as dyslexia, as once commonly thought. There is a difference between Irlen Syndrome and visual information processing. While visual information processing disorders are commonly accepted, Irlen Syndrome is still considered ‘fringe’ and mostly because both the diagnosis system and treatment is proprietary (i.e. marketed under and protected by the Irlen Institute). The fact that it is commercial makes it difficult for the science community to accept. This means that the only information and studies about Irlen Syndrome, especially versus visual information processing and dyslexia, is written by the Irlen Institute.

There are similar results being seen with a process called Intuitive Colorimetry by the British Medical Research Council and this is the process that most research is using to try and understand better the effect of colour on neurological processes.

The effect of colour as a treatment to patients is that a visual processing disorder results from the brain not being able to process visual information properly, for whatever reason (e.g. acquired head injury/learning difference etc.). There are a number of ways in which we can alter or manipulate the way the brain processes this information so we can make it easier to process. Colour is one of those ways. The fact you need coloured lenses is not a diagnosis in itself, contrary to Irlen Syndrome.

The use of tinted lenses is one of many tools to help the brain process visual information better. Irlen Syndrome is not thought to be a unique condition on its own, but the use of coloured lenses can be a very effective treatment for the right individual.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0Cqkm8D90M (Irlen’s Video)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental diversity. This means that the ADHD brain is different to the neurotypical brain and it develops or matures at a slower rate.

Research has shown that the ADHD brain is comparatively smaller in some areas, functions and operates differently and it’s chemical messenger or neurotransmitter system for dopamine is affected. Although ADHD does not influence intelligence, there is still much more research needed to fully understand these differences.

Areas of the brain that are affected by these differences are responsible for:

- Attention

- Problem solving

- Memory

- Language

- Motivation

- Judgement

- Impulse control

- Behaviour

- Emotion

- Energy or Motor control

- Executive functioning – which includes your ability to plan and organise.

As a consequence, this neurodevelopmental delay makes automatically controlling and filtering attention, behaviours, emotion etc. more challenging. This means that the ADHD brain may have to work much harder to control aspects that come naturally to others and can result in the ADHD individual experiencing significant fatigue by the end of the school or working day.

When diagnosed, ADHD individuals usually fit into three groups or subtypes. This recognises the fact that even though there are some common factors with a diagnosis of ADHD, everyone is different and unique.

The ADHD subtypes are:

- Inattentive ADHD

- Hyperactive and Impulsive ADHD

- Combined ADHD

Inattentive ADHD

Inattentive ADHD can cause individuals to make careless mistakes because they have difficulty maintaining attention, following detailed instructions and organising tasks and activities. They have a weaker working memory, are easily distracted and often lose things.

Although the main characteristics are a lack of control of attention, focus and concentration, some impulsivity, behavioural and emotional activity and executive dysfunction are often also experienced but to a much lesser degree.

This ADHD subtype used to be known as ADD and is more commonly diagnosed in girls, adults, those who have had a frontal lobe head injury and those who are autistic.

Hyperactive and Impulsive ADHD

Hyperactive and Impulsive ADHD causes individuals to feel the need to constantly move. They often fidget, squirm and struggle to stay seated. They may talk non-stop, interrupt others, blurt out answers and struggle with self-control.

Children can exhibit high activity levels such as running, climbing and moving around as well as impulse actions which can lead to social behavioural problems. As the brain matures in adolescence and adults, so does the ability to control and the hyperactivity turns from major movement to more minor restlessness and fidgeting.

The main characteristics include a lack of control of behaviour, increased activity levels and acting on impulse without thinking or control. Inattentiveness and executive dysfunction are often also present, though generally to a lesser extent.

This ADHD subtype is more recognisable and is more often diagnosed in children and men.

Combined ADHD

Combined ADHD is a combination of Inattentive ADHD and Hyperactivity and Impulsive ADHD. The main characteristics include a lack of control of attention, behaviour, activity and impulses. They are all present in fairly equal measures.

There are plenty of highly successful individuals with ADHD who direct their energies, enthusiasm and creativity to the advantage and benefit of society. Not every person with ADHD has the same personality traits and this means that despite some challenges, there can be many benefits and advantages unique to each individual.

These strengths may include high levels of intuition, creativity, energy, spontaneity, lateral thinking and the ability to hyper-focus on tasks and areas of interest.

This ability to hyper-focus can be extremely advantageous as it can allow the person to comprehensively concentrate on the task in hand, without even noticing what is going on in the world around them. This can lead to tasks being completed quickly and can also lead to expert level knowledge in an area of interest.

Their strong creativity, energy and intuition can mean that they can be good problem solvers, entrepreneurial and very insightful. They often have a great sense of humour and can be extremely empathetic, loyal, trusting, forgiving and tenacious.

ADHD can often coexist with other neurodiversity and affects 2-5% of all children.

Some of the many benefits of neurodiversity

Based on the work of Mary Colley, Founder of the Charity DANDA (Developmental Adult Neurodiversity Association).

1 in 5 children are neurodivergent

- Studies suggest the rate of mental health problems in people with a learning difference is double that of the general population.

- An estimated 10% of the New Zealand population is dyslexic, yet percentages climb as high as 90% in our prisons.

- About 50% of students with dyscalculia are also likely to have dyslexia.

- Research shows that 80% of children who have reading difficulties also lack the basic visual skills required for reading.

- The school dropout rate of dyslexic students can be as high as 35%, twice as high as the national average of many countries.